A friend of mine recently shared an exciting decision made by her therapist, who recognized her deep exhaustion as a young mother of twins. The therapist introduced a practice where my friend would sit in an armchair in the therapist’s garden for an hour before each therapy session. This experience taught my friend the importance of finding a safe space for herself, which ultimately benefits her ability to be a stable and nurturing mother to her children.

Exhaustion and Burnout in Parents

Parents, especially mothers, often experience exhaustion and burnout when raising young children. In recent decades, the burden on parents has increased due to the reduced influence of extended family support in our society. Today, most parents raise their children within the confines of the nuclear family, placing a heavy responsibility on mothers for their child’s emotional development.

The Need for a Comprehensive Network of Care

Contrary to the belief that a child’s emotional development solely depends on their relationship with the mother, anthropological studies reveal that children benefit from a more comprehensive network of caregivers. In cultures where multiple caregivers are involved in caring for the baby, the phenomenon of “fear of strangers” is less prevalent. Additionally, social anxiety in later years is also less frequent in these societies.

Seeking Help and Support

It is crucial for parents to recognize the importance of seeking help and support from others. By involving other caregivers such as fathers, grandparents, aunts, uncles, friends, and even paid helpers, parents can create better conditions for their own stability and well-being. Even modest support can have a significant impact on both parents and children.

Encouraging Social Interaction and Support

Creating opportunities for social interaction and support among parents can be beneficial. For example, parenting coaches may organize events or activities where mothers with their babies can interact with each other. These experiences can help mothers realize the value of connecting with others and seeking additional forms of contact and support.

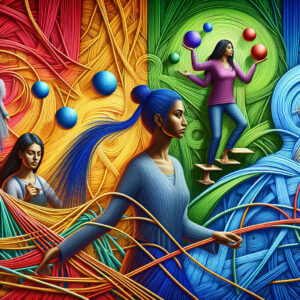

Carving Out a Protected Space

Parents need to carve out a protected space for themselves, both physically and emotionally. This includes having a corner of their own, allowing themselves the rest they need, and reducing their total availability to their child when necessary. When parents guarantee a safe space for themselves, it enables their child to develop the vital skill of self-soothing.

Teaching Self-Soothing Skills

Research on infants with sleeping problems has shown that teaching parents to reduce their total availability when the baby cries can improve sleep patterns. Instead of immediately picking up the baby, parents are encouraged to provide comfort while sitting by the baby’s side. This helps the baby learn to self-soothe and fall asleep more easily.

Involvement of Fathers

The involvement of fathers in creating a safe space and teaching self-soothing skills yields better results. When fathers actively participate in the process, the child’s sleep improves even further. This highlights the importance of both parents in building a protected space for themselves and conveying safety to their children.

The Link to Reducing Children’s Anxiety

Creating a safe parental space is also crucial in reducing a child’s anxiety. In my next post, I will delve into this subject further. By providing parents with a protected space, we can significantly impact a child’s fears and anxieties.

Conclusion

Recognizing the need for a safe space for parents is essential in promoting their well-being and their ability to provide stable and nurturing care to their children. By seeking help, involving others, and carving out a protected space, parents can create an environment that fosters both their own stability and their child’s development.